HISTORY OF YSB

Background & Significance of

The Yokohama Specie Bank, Ltd

to the Japanese Diaspora Community

This site is currently in beta.

We welcome your feedback and please come back for future developments.

Email us at jaha@jcccnc.org or call 415.567.5505.

The JAHA collection houses invaluable historical documents from the San Francisco branch of the Yokohama Specie Bank (YSB). It might seem surprising that the history of this global foreign exchange bank, pivotal in supporting the Japanese Empire's expansion, intersects with the lives of Japanese immigrants in California. However, for these immigrants, often excluded from loans by non-Japanese financial institutions, YSB branches were lifelines.

Delving into the JAHA collection reveals a vital facet of immigrant history: the economic foundations supporting immigrants' daily lives in their new homes. A poignant example is the "hometown" remittance application, which highlights how immigrants maintained connections with their homeland through remittances via YSB. Additionally, documents related to the operation of Japanese-language schools like Kinmon Gakuen showcase immigrants' resilience in navigating political and economic challenges.

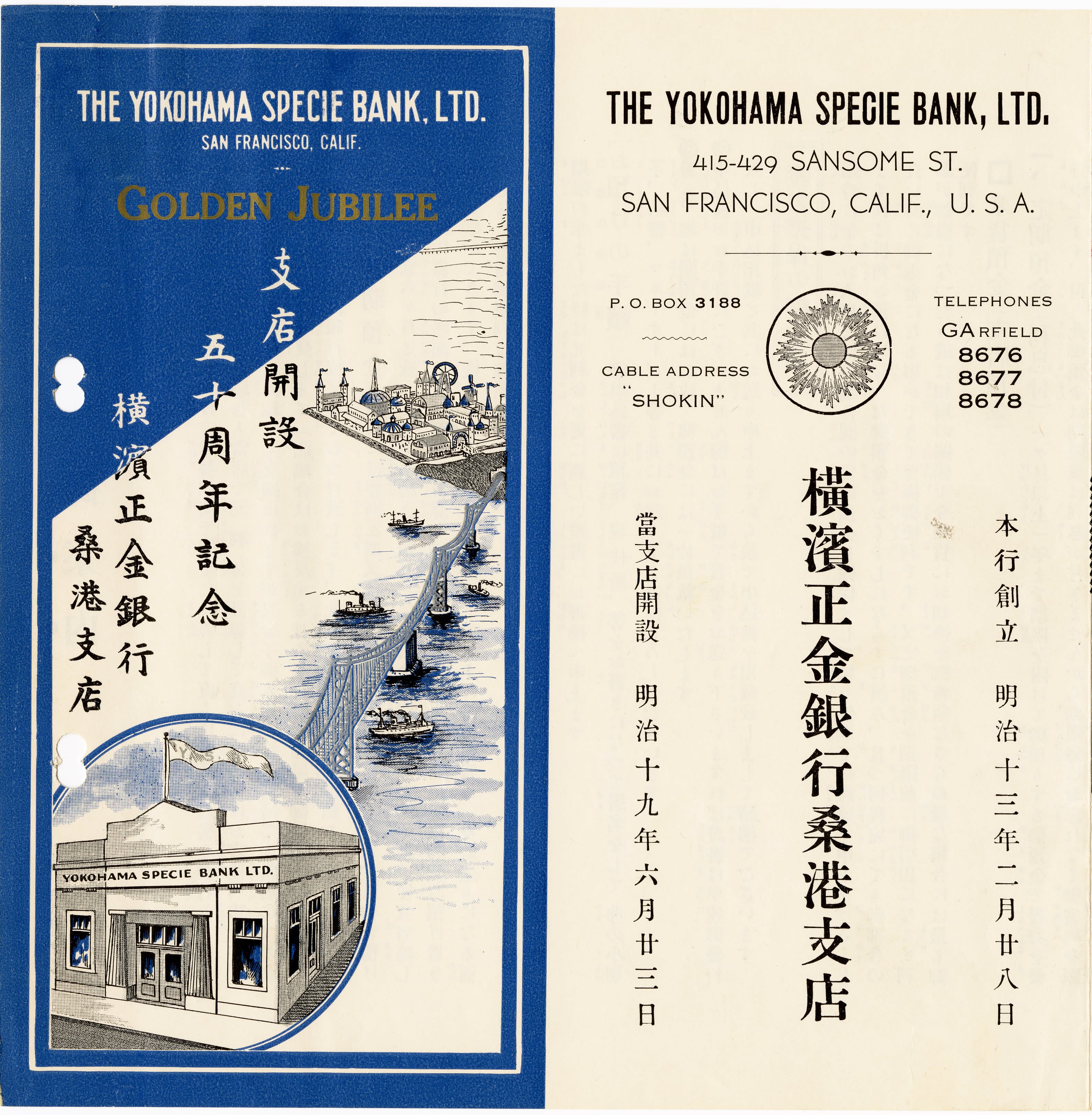

In 1936, the San Francisco YSB branch celebrated its 50th anniversary with a glamorous brochure, intertwining 50 years of operation with both Japanese American and Japanese financial history.

Among these intriguing documents, a letter stands out, capturing the author's imagination. This letter, dated January 4, 1915, from Kiyotaro Aoki of the Honolulu YSB branch to Junzo Fujihira in San Francisco, thanks the San Francisco Japanese Association for promptly sharing its bylaws. Aoki expresses the desire for a similar association in Honolulu, illustrating the interconnectedness of Japanese immigrant communities across the Pacific.

Even after the Gentlemen's Agreement restricted movement between regions, immigrant activities continued to bridge North America and Hawaii. The strategies of each YSB branch played a pivotal role in this connection. So, why did YSB branches foster such connections between Hawaiian and Californian immigrants? It wasn't mere kindness; it was part of YSB's broader role in Japan's Pacific expansion since the 19th century, closely tied to Japanese migration. Understanding this history sheds light on the bank's purpose in facilitating these immigrant connections.

History of the YSB

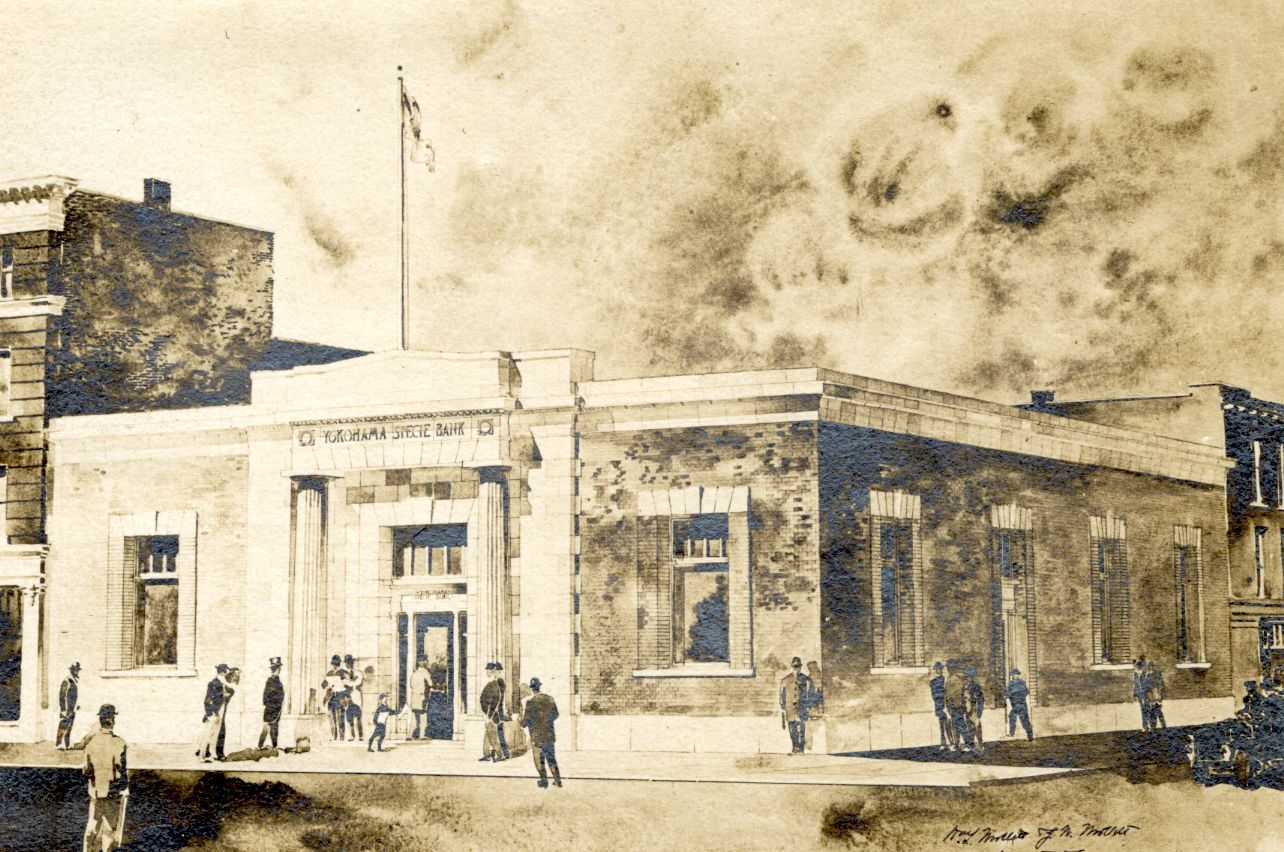

The San Francisco branch of the Yokohama Specie Bank (YSB) provides a captivating glimpse into the Japanese American community and US-Japan relations prior to World War II. Established in 1879 and commencing operations in February 1880 at the dawn of Japanese modernity, this institution served as the flagship bank supporting international trade and the financial needs of the Japanese government abroad. Over the years, YSB grew to become one of the world's largest foreign exchange banks with branches all over the world until it ended its 60-year history when it was reorganized as a private bank after the second world war in 1946.

YSB Records, JAHA, JCCCNC

YSB Records, JAHA, JCCCNC

In addition to its well-recognized focus areas as a foreign exchange bank centering around the New York and London markets1 (internationalism)2 and a bank supporting the Japanese government’s colonial ambitions in Asia (imperialism), it also provided basic and important services to Japanese immigrants in the Asia Pacific region (trans-nationalism). This trans-nationalism was a significant aspect of its mission.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Image Source: Wikipedia

Original YSB Branch in Yokohama, Japan

The intricate interweaving of these functions became evident through various offices and branches which facilitated these roles on local and regional levels abroad. Although these branches could and did, at times, operate with differing priorities, the overall operations of the YSB were connected on a global scale, with each branch driven by the needs and circumstances on the ground.

YSB Branch Network

YSB West Coast Hub

Image source: San Francisco Public Library

Image source: San Francisco Public Library

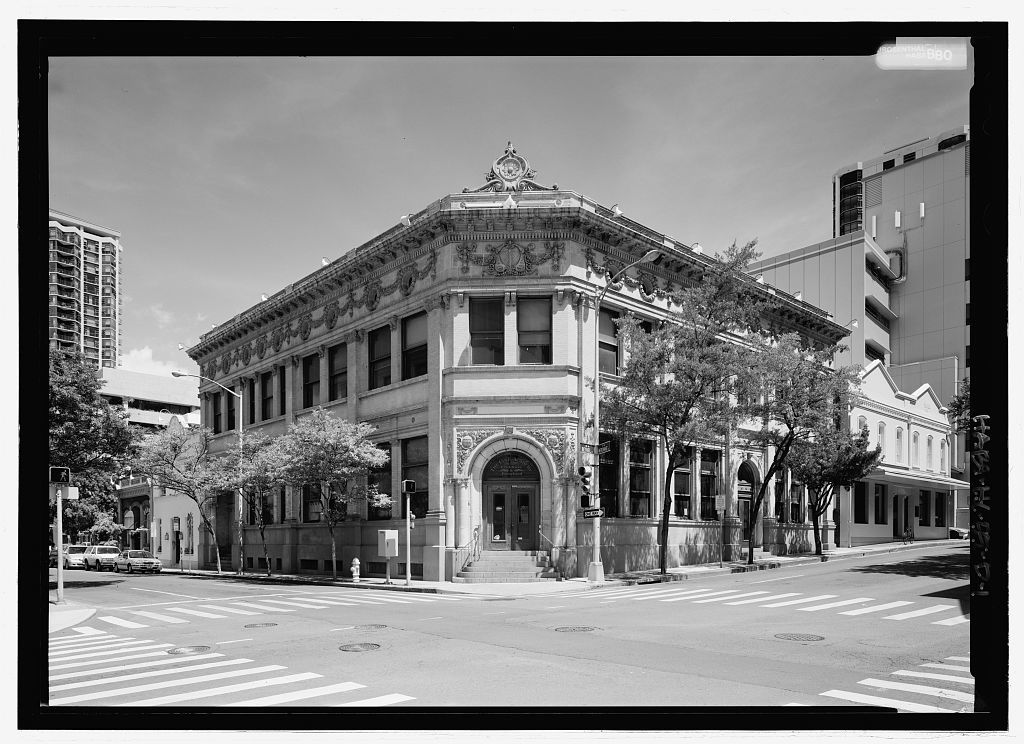

San Francisco YSB Branch located at Sansome, corner of Commercial Street

The San Francisco branch, positioned as the central hub on the West Coast of North America, played a pivotal role in overseeing the bank's operations in Honolulu and Los Angeles. The San Francisco branch's journey began in 1886 when it was initially designated as a sub-branch under the jurisdiction of the London branch. While originally intended for US-Japan trade transactions, it soon pivoted toward serving the needs of immigrants, especially in its role of facilitating the remittance of funds for Hawaiian government-sponsored immigrants (官約移民), which had begun in 1885.

Image source: Library of Congress

Image source: Library of Congress

YSB Honolulu Branch located at Merchant & Nuuanu Streets

In 1896, the San Francisco sub-branch attained independent status, breaking free from London's oversight. It maintained close ties with Honolulu, which, in turn, had its own sub-branch status promoted to a branch in 1897. As Japanese immigration to the West Coast surged, the YSB expanded its offices3. By 1920, the total deposits at the head office collected from Hawaii, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle reached over 50 million yen, further highlighting its significance.

Dennis M. Ogawa Nippu Jiji Photograph Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Dennis M. Ogawa Nippu Jiji Photograph Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives

View of the front doorway of YSB Honolulu Branch

Despite the growth of the Pacific Coast branches, there were disagreements between the headquarters in Yokohama (later Tokyo) and the branches in San Francisco, Honolulu, and sub-branches in Los Angeles and Seattle concerning their dealings with immigrants. The bank's policies, especially those of Yokohama, often favored internationalism and imperialism over support for Japanese American businesses, creating a divide between the two.

Compared to YSB branches in China and Manchuria4, the volume of deposits and remittances from the Japanese American community that the YSB on the West Coast could absorb was limited. However, its ability to deal in dollars and use them for foreign exchange transactions was essential. Unfortunately, the bank's reluctance to provide loans to local immigrants often led to dissatisfaction among the members of the Japanese American community, as they saw themselves being the ones who were providing needed funds but who were receiving little in return, thus creating an asymmetrical relationship.

The turning point in this relationship occurred during the financial panic of 1907 that affected New York and Chicago and which spilled over into the San Francisco business community. Because of the panic, Japanese financial institutions, including Kinmon Bank 金門銀行 and Nichibei Bank 日米銀行, failed, leaving only two Japanese immigrant banks in California: Nippon Bank 日本銀行in Sacramento and Fresno Kangyo Bank 布市勧業銀行 in Fresno. The consulate sought the YSB's assistance in bailing out these banks. Although YSB granted a loan of nearly $70,000 to the Nichibei Bank, the YSB's stance remained largely passive, emphasizing its reluctance to lend a significant amount of money to the Japanese American community5.

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC

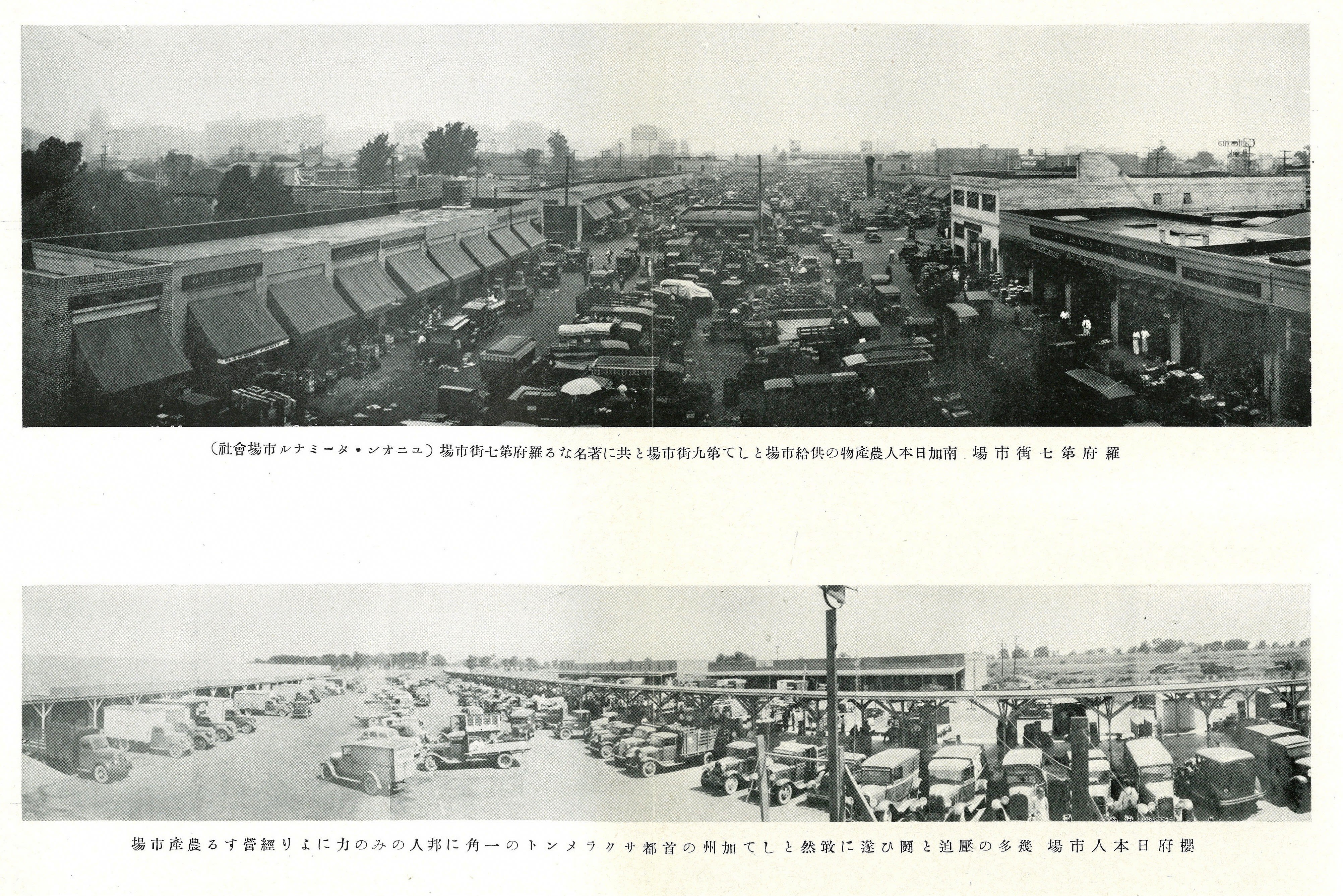

Japanese American farm market in Sacramento, CA

YSB benefited from a series of bank failures in 1909, so that after the disappearance of the major immigrant banks by 1911, YSB branches in San Francisco and Los Angeles virtually monopolized immigrant deposits ($11 million in 1913). Ironically, the Japanese farmers of the time had developed a microfinance system of their own, such as the tanomoshiko 頼母子講, and thus were not totally dependent on Japanese immigrant banks.

Nonetheless, the San Francisco branch of YSB found itself compelled to heed the directives from its headquarters, which looked askance at supporting immigrant businesses. This led to the refusal of a $30,000 loan request from a Japanese grape grower in 1913 and a $56,000 loan application from Kyutaro Abiko in 1914, both of which had been guaranteed by the Japanese consul.

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC.

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC.

Kyutaro Abiko 安孫子 久太郎

However, the attitude of YSB began to shift after the enactment of the Alien Land Act in 1913, which triggered a crisis within the Japanese immigrant community. By May 1918, the board of directors at YSB approved a pivotal resolution to extend loans to branches in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Honolulu. These loans were specifically designated as "long-term special loans to Japanese Americans operating agricultural and industrial businesses," signaling a heightened awareness of the dissatisfaction among Japanese immigrants who had felt they were only good for making deposits. Even with this change in attitude by the Board, the total funds allocated for these loans amounted to only 300,000 yen, underscoring the ongoing challenge in striking a balance between the interests of the foreign exchange bank and those of the Japanese immigrant community.

In contrast to the YSB, the Japanese consulates consistently maintained that the failure of Japanese financial institutions could have adverse repercussions on the local community's development, a situation that could warrant potential bailouts. This perspective was echoed by Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) leadership.

Simultaneously, a similar sentiment arose among Issei leaders who, grappling with the effects of the Gentlemen's Agreement and the 1907 Depression, sought to fortify their position. This movement culminated in the formation of the Japanese Association of America in 1908. This association was comprised of immigrant elites and representatives of Japanese companies residing in San Francisco who were aiming to consolidate their political and economic influence through the exercise of "certifying power" on behalf of the consulate.

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC

First coastal Japanese Association meeting held in Portland, OR (1914)

Notably, Taro Hozumi 穂積太郎, the manager of the San Francisco branch of YSB, played a pivotal role, in collaboration with Kinji Ushijima牛島謹爾, known as the "Potato King," in the implementation of this consulate-orchestrated immigration initiative. During the nascent stages of the Japanese Association in America, entities like YSB, Mitsui & Co., and Toyo Kisen Co., collectively known as the "Big Three," held a significant and influential position.

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC

Zaibei Nihonjinshi / 在米日本人史, (1940, San Francisco, CA). The English translation by Seizo Oka, JAHA, JCCCNC

Kinji Ushijima牛島謹爾

This pattern can be seen in the preceding case of the Honolulu Japanese Chamber of Commerce, which was founded in 1900 and evolved into the precursor of the modern Honolulu Japanese Chamber of Commerce. Its establishment was a result of a collaborative effort between the consul general, YSB branch managers, and Issei leaders, illustrating that these branch managers were members of the local community and, to some extent, wielded a degree of autonomy apart from the directives of the head office6.

The same theme manifested itself in California, shown by an anecdote involving a YSB Los Angeles branch manager who, in the early 1930s, resigned from his position after he unilaterally approved a loan to a Japanese businessman, despite the disapproval of YSB headquarters. Unfortunately, this loan ultimately proved unsuccessful, highlighting the tension between local autonomy and corporate headquarters' control.

A document about the organizational bylaws of the Japanese Association in America and San Francisco, the San Francisco branch manager’s mediation, and an idea to model after the Japanese Association in San Francisco.

Transcription:

「在米日本〔人〕会及桑港日本人会の規約其他の参考書類、早速同会より直送を蒙り難有〔ありがたく〕奉存〔ぞんじたてまつり〕候。御承知の通り、当地は豪傑連中々沢山有之〔これあり〕、容易に評議相纏り不申〔もうさず〕、乍併〔しかしながら〕其内貴地日本人会に似寄もの産出致可申〔いたしもうすべく〕と期待致居〔いたしおり〕候。」

Translation:

I am very grateful for receiving the bylaws of the Japanese Association in America and the Japanese Association in San Francisco, as well as other reference documents, directly from the said association. As you are aware, there are many men of strong opinions in this area, and it is not easy for us to discuss these matters, but we hope that something similar to the Japanese Association in San Francisco will soon be produced.

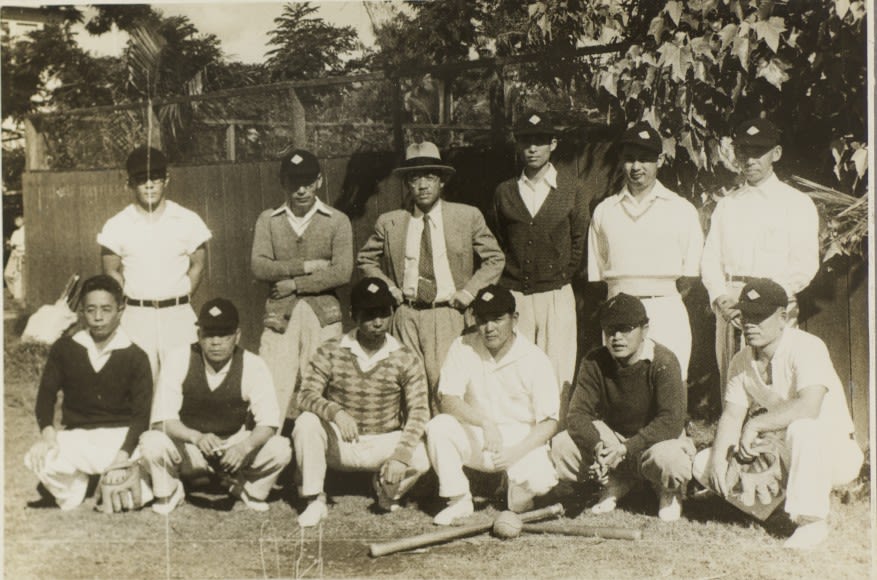

Honolulu Japanese Senior Business Baseball League: YSB Team

Remittances

Although the home office of YSB did not generally approve of making loans to the immigrant community, the San Francisco branch had been steadily cultivating deep connections with the Japanese Americans by offering long-term loans to Japanese immigrants and facilitating remittance and deposit services to Japan from the 1910s through the 1920s. However, the definitive turning point came in 1931 with the reintroduction of gold embargo, a move that led to a bolstering of the dollar's strength against the yen.

Consequently, the San Francisco branch experienced a substantial surge in dollar deposits during this period. A key factor that aided YSB in capitalizing on this opportunity was its strategic decision to advertise a more attractive interest rate on dollar deposits compared to yen deposits. This move was instrumental in setting YSB apart from its rival, Sumitomo Bank.

The substantial surge in dollar deposits from Japanese immigrants brought much-needed relief to YSB, which had been grappling with tight overseas funds. Notably, as noted above, the bank's previous practice of actively accumulating deposits while passively lending had faced criticism. However, with the changing dynamics, YSB could now rally around the "patriotic" slogan, successfully mobilizing dollar funds from Japanese Americans to aid in replenishing Japan's foreign currency reserves.

A “hometown” remittance application showing Tameichi Asano sent $25.86 from Los Angeles to Mikio Asano in Tokyo via YSB on August 19, 1938.

Sender: Tameichi Asano

Recipient: Mikio Asano, Takeo Miki's residence, 305 Sanya, Yoyogi, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo

Remittance amount: 93 Japanese yen

The depreciation of the yen also had significant implications for the Japanese American community, as it incentivized more Nisei (children of Japanese immigrants) to pursue higher education in Japan. This was driven by the lure of lower tuition fees when paid for in yen.

In the grander scheme, YSB's increasing focus on Japan-centric policies resulted in a capital outflow from the Japanese American community to Japan, which in turn hindered the further economic development of the Japanese American community.

YSB records, JAHA, JCCCNC

YSB records, JAHA, JCCCNC

YSB San Francisco Branch Brochure, 1936

In 1941, as the U.S. government's decisive action against Japan loomed on the horizon, YSB, especially its New York branch, made frantic efforts to liquidate and divest its dollar funds. The bank's six-decade history met a sudden and decisive conclusion on July 26 when its assets were frozen, effectively severing economic ties with both Europe and the United States. The ultimate destination of the immigrant funds held by YSB remains a mystery. Amid the backdrop of the Japanese government's increasingly expansionist orientation, YSB's role as a bank serving the needs of immigrants took a backseat to the broader ambitions of the empire.

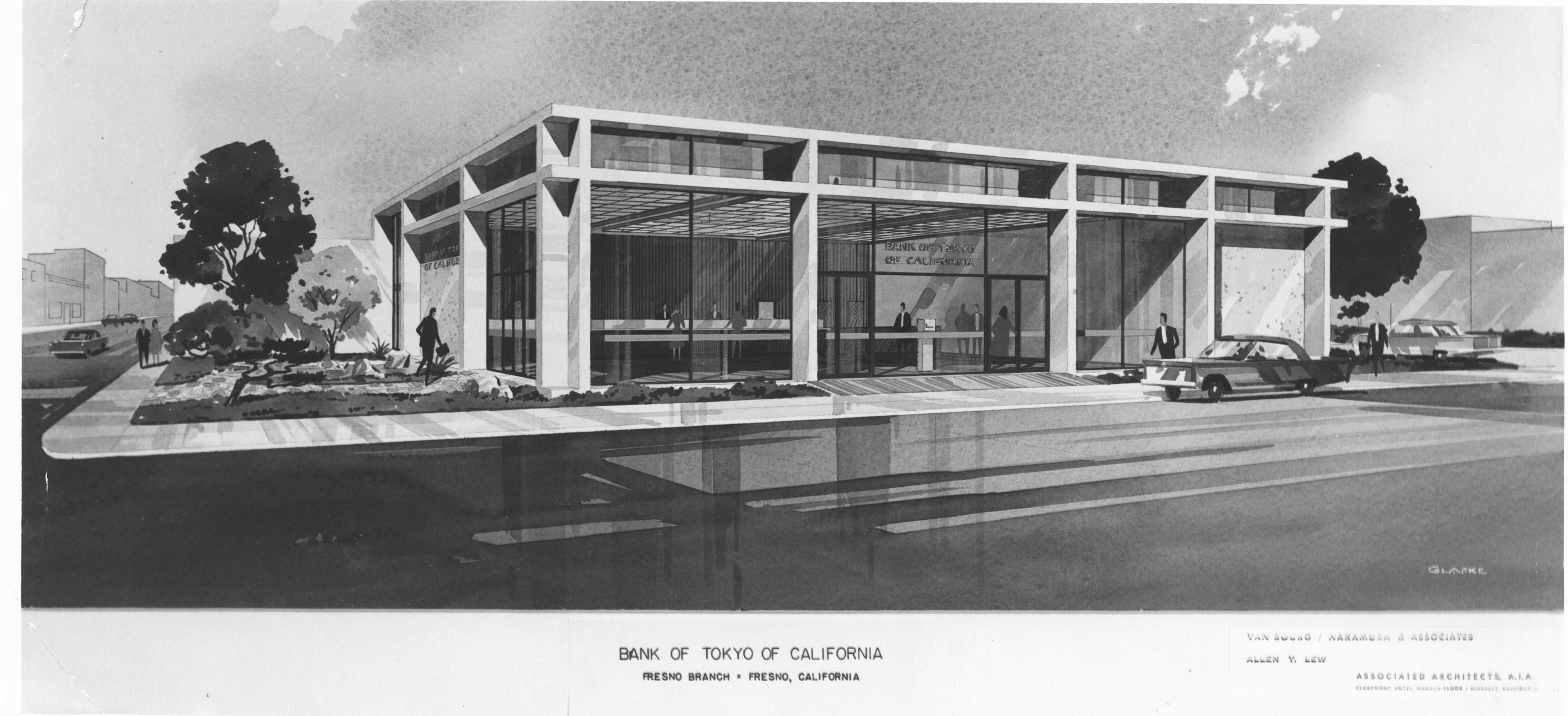

Nevertheless, history rarely unfolds in a straightforward manner. After World War II, its role in serving immigrant communities underwent a remarkable resurgence, both in scope and significance. This revival came to fruition when the New York branch of the Bank of Tokyo (BoT) reopened its doors in 1952. BoT, inheriting YSB's funds and supplemented by half of the capital contributed by Nikkei (Japanese emigrants and their descendants residing in foreign countries) leaders in California and Hawaii, embarked on a transformative journey. In response to the requests of Nikkei leaders in these regions for a local presence, the San Francisco branch was established in 1953.

By attracting this localized investment and ordinary Nikkei depositors as customers, the Bank of Tokyo was able to expand its branch network, incorporating numerous Nikkei communities throughout California.

YSB Records, JAHA, JCCCNC

YSB Records, JAHA, JCCCNC

Bank of Tokyo of California,

Fresno Branch

YSB's earlier rush to accumulate deposits for the sake of empire expansion had, at times, created significant tensions within the local community. However, in 1954, a new chapter was initiated for the Nikkei community and Japanese banking. Distinguishing itself from YSB, which had at times been ensnared by other agendas of the Empire, the Bank of Tokyo, designated as a specialized foreign exchange bank, paved the way for a fresh beginning.

References

・Mitani, Taichirō 三谷太一郎(1975)Wōru Sutorīto to Kyokutō : seiji ni okeru kokusai kinʼyū shihon ウォール・ストリートと極東:ワシントン体制における国際金融資本の役割. Chūō Kōron中央公論: 90(9)、later published as Mitani Taichirō 三谷太一郎(2009) Wōru Sutorīto to Kyokutō ウォール・ストリートと極東. Tokyo : Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppanka東京大学出版会.

・Ichioka, Yuji (1977), “Japanese Associations and the Japanese Government: A Special Relationship, 1909-1926”, Pacific Historical Review, 46(3)

・Kitaoka, Shin'ichi 北岡伸一(1978)Nihon Rikugun to tairiku seisaku : 1906-1918-nen 日本陸軍と大陸政策:1906-1918年. Tokyo: Tōkyō Daigaku Shuppanka 東京大学出版会.

・Taira, Tomoyuki 平智之(1982)”Nihon teikoku shugi seiritsu-ki, Chūgoku ni okeru Yokohama shōkin ginkō 日本帝国主義成立期、中国における横浜正金銀行”, Tōkyō Daigaku Keizai-gaku Kenkyū東京大学経済学研究:25.

・Kimura, Kenji 木村健二(1985)“Keihin ginko no seiritsu to hōkai: Kindai nihon imin-shi no ichi-sokumen 京浜銀行の成立と崩壊:近代日本移民史の一側面”, Kinyū Keizai金融経済:214.

・Takashima, Masaaki 高嶋雅明(1986)”Daiichijisekaitaisen mae no Karuforunia ni okeru nihonjin kin'yūkkan 第一次世界大戦前のカルフォルニアにおける日本人金融機関”,Kinyū Keizai金融経済:216

・Ichioka, Yuji (1988), The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese Immigrants, 1885-1924. New York :The Free Press.

・Taira, Tomoyuki 平智之(1989)”Kin-kaikin zengo no Yokohama shōkin ginkō金解禁前後の横浜正金銀行“, Shi-shi Kenkyu Yokohama 市史研究よこはま:3.

・Takashima, Masaaki高嶋雅明(1992)” Senzen-ki Shiatoru ni okeru nihonjin kin'yūkkan 戦前期シアトルにおける日本人金融機関”, Keizai Riron 経済理論 :248.

・Takashima, Masaaki 高嶋雅明(1993)”Senzen-ki Kariforunia ni okeru Yokohama shōkin ginkō to nikkei shakai: 1900 ~ 1935戦前期カリフォルニアにおける横浜正金銀行と日系社会:1900~193”, Osaka Economic Papers大阪大学経済学Vol. 42, no. 3-4.

・Yasaki, Noritaka 矢ケ崎典隆(1993)Imin nōgyō: Kariforunia no nihonjin imin shakai 移民農業:カリフォルニアの日本人移民社会. Tokyo 東京:Kokon Shoin 古今書院.

・Taira, Tomoyuki 平智之(1993)”Keizai seisaika no Yokohama shōkin ginkō: Nyūyōku shiten o chūshin to shite 経済制裁下の横浜正金銀行:ニューヨーク支店を中心として”, The bulletin of Yokohama City University Social Science 横浜市立大学論叢 社会科学系列. 44:1-3.

・Taira, Tomoyuki 平智之(1995)”Nitchūsensō-ki no nichiei keizai kankei to Yokohama shōkin ginkō Rondon shiten日中戦争期の日英経済関係と横浜正金銀行ロンドン支店” The bulletin of Yokohama City University Social Science 横浜市立大学論叢 社会科学系列. 46:2-3.

・Azuma, Eiichiro (2005), Between Two Empires: Race, History, And Transnationalism In Japanese America(New York:Oxford University Press)

・Nishimura, Shizuya (2012), “The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, 1870–1913” in Nishimura, et al. (eds.), The Origins of International Banking in Asia: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (New York: Oxford University Press)

・Horesh, Niv (2015), “Competing Imperial Banking: The Yokohama Specie Bank and HSBC in China – 1919 as a Watershed?”, in Hubert Bonin, Nuno Valerio, & Kazuhiko Yago (eds.), Asian Imperial Banking History (London: Routledge)

・Hegwood, Robert A. (2018), “Transpacific Foundations for Growth: Migrant Brokers and Japan’s Rise as a World Power, 1868-1964 “, Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania

・Azuma, Eiichiro (2019), In Search of Our Frontier: Japanese America and Settler Colonialism in the Construction of Japan’s Borderless Empire (University of California Press)

・Schiltz, Michael.(2020), Accounting for the Fall of Silver: Hedging Currency Risk in Long-Distance Trade With Asia, 1870-1913(Oxford: Oxford University Press)

・Shiratori, Keishi 白鳥圭志(2021)Yokohama Shōkin Ginkō no kenkyū : gaikoku kawase ginkō no keiei soshiki kōchiku 横浜正金銀行の研究:外国為替銀行の経営組織構築. Tokyo 東京:Yoshikawa Kōbunkan吉川弘文館.

・Tsukino, Fūko 月野楓子(2022)‘Yoridokoro’ no Keisei shi: Aruzenchin no Okinawa imin shakai to zai-a Okinawa ken-jin rengokai no setsuritsu 「よりどころ」の形成史:アルゼンチンの沖縄移民社会と在亜沖縄県人連合会の設立. Yokohama 横浜:Shunjū sha春風社.

・Izumo, Yūichiro 出雲勇一郎(2022)”Senzen-ki Shiatoru ni okeru nikkei imin to kin'yūgyō: Taiheiyō shōgyō ginkō no keisei to satetsu 戦前期シアトルにおける日系移民と金融業:太平洋商業銀行の形成と蹉跌” Asia・Culture・History アジア・文化・歴史. Vol. 13.

・Fukuda, Masato 福田真人(2022)”Meiji 14-nen seihen zen'ya ni okeru ōkuma shigenobu no junbikin kaishū seisaku: Kōgyōshōkai kara Yokohama shōkin ginkō e 明治14年政変前夜における大隈重信の準備金回収政策:広業商会から横浜正金銀行へ” in Keizai no ishin to shoku kōgyō 経済の維新と殖産興業:1859~1890, ed. Suzuki Jun 鈴木淳. Tokyo: Mineruva Shobōミネルヴァ書房.

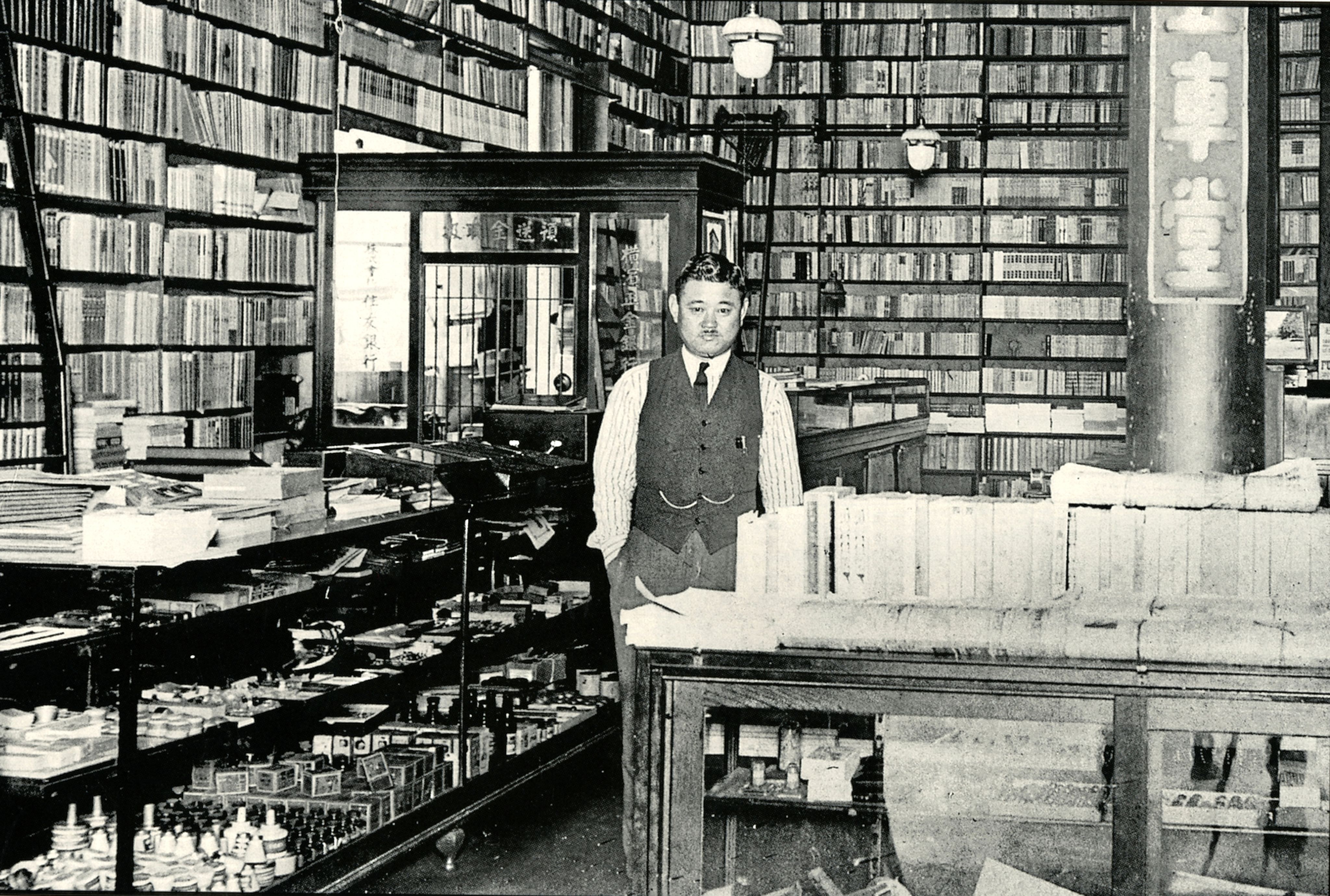

The records of the Yokohama Specie Bank's (YSB) 横浜正金銀行 San Francisco branch, currently housed in the Japanese American Historical Archives - Seizo Oka Collection (JAHA) at the Japanese American Cultural Center of Northern California (JCCCNC), provide a unique window into the inner workings of the Japanese American business community. This aspect of history is often overlooked in traditional historical accounts, offering a nuanced understanding of the Japanese American community, its intricate social networks, hierarchical structures, business objectives, and entertainment activities during the era of prohibition.