Early History of

San Francisco’s Japanese Immigrant Community

This site is currently in beta.

We welcome your feedback and please come back for future developments.

Email us at jaha@jcccnc.org or call 415.567.5505.

Housed in San Francisco at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California (JCCCNC), the Japanese American Historical Archives-Seizo Oka Collection (JAHA-Oka) is a rich repository of prewar Japanese immigrant materials— historical documents that were thought at one time to have been mostly lost due to the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Leading a one-person crusade for the preservation of Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) history, the late Mr. Seizo Oka diligently collected what was still available in the postwar Japanese American community and thereby built an impressive archive of immigrant-era primary source materials that dwarfs most academic library and archival collections in the continental United States. Offering a historical overview of San Francisco’s Japanese community from its inception through its heyday in the 1920s, this essay draws from some of the JAHA-Oka materials, such as the massive 1,300-page “History of Japanese in America” (Zaibei Nihonjinshi) that was compiled in 1940 by the Japanese Association of America (see below) under the initiative of San Francisco Issei leaders1.

With the realization that the preservation of historical source materials is essential to the creation of history itself, it is my hope that this essay will contribute to the public awareness of the importance of the JCCCNC’s endeavors to create a community-based historical archive that is open not only to academics but also to the general public, especially Japanese Americans. As readers will learn in this short essay, San Francisco has been an economic, political, and cultural hub of Japanese American society for more than one hundred fifty years . The JCCCNC archives constitute yet another example of San Francisco’s central place and role in the preservation of Japanese American history, identity, and community ties.

The Beginnings

1870s

San Francisco is indeed the place where Japanese America can be said to have originated, tracing its history back to the 1870s when the first Japanese immigrants arrived. As the primary West Coast hub that connected America to Asia since the mid-nineteenth century, the Golden City attracted many immigrants from across the Pacific, especially Chinese who began arriving in the 1850s.

In 1873, the local Japanese consul reported the presence in San Francisco of

sixty-eight men, eight women, and four children of Japanese origin.

Five years later, under the auspices of that diplomat, the first known “community” event was held to celebrate the birthday of Emperor Meiji, and some eighty Issei showed up2. These local Japanese residents included a group of Christian converts—young men who had come as ambitious self-supporting students in pursuit of modern/western knowledge and the frontier experience. In 1877, they organized the first Japanese American organization called the Gospel Society (Fukuinkai) that met in the basement of the Chinese Mission in Chinatown3. Some members of this society later became prominent leaders of San Francisco’s Japanese community, including Kyūtarō Abiko, publisher of the Nichibei Shimbun (Japanese-American News) and a founder of Japanese farm settlements in Livingston and Cortez, California4.

The Entrepreneurs

1880s

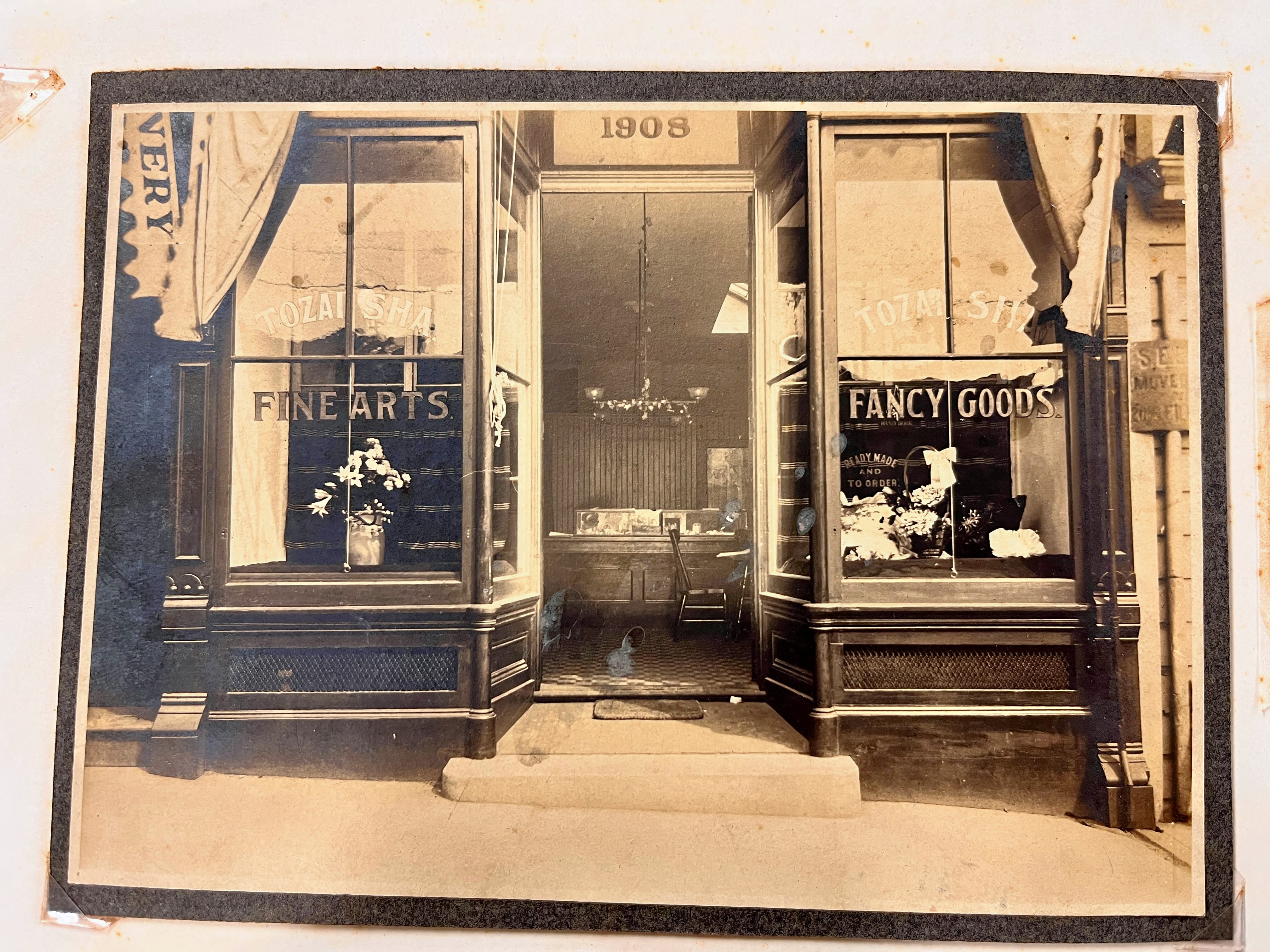

As a commercial hub for US-Asia trade, San Francisco attracted many entrepreneurially-minded Japanese, who not only pioneered commercial activities by Asian immigrants in the continental United States but also the import/export business with Japan. In 1886, a few Issei opened Japanese art-and-curio shops and general merchandise stores that catered to the local white middle-class.

Tozaisha & Co. located at 1908 Fillmore Street, San Francisco. One of the early Japanese American fancy goods stores catering to white American customers. JAHA Collection and the Takeshia and Teraoka family papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Tozaisha & Co. located at 1908 Fillmore Street, San Francisco. One of the early Japanese American fancy goods stores catering to white American customers. JAHA Collection and the Takeshia and Teraoka family papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives

The same year saw the opening of the San Francisco Branch of the Yokohama Specie Bank (YSB)—a state-backed financial institution that was entrusted with the mission of promoting international trade on behalf of Japan (see Maeda essay)5. The simultaneous establishment of the first ethnic businesses and the YSB branch anticipated the inseparable relations between the local Japanese immigrant economy and the bank—the latter being an important source of capital and guidance when virulent racism made it difficult for the Issei to secure loans from white-owned financial institutions.

Yokohama Specie Bank, San Francisco Branch, YSB Records, JAHA, JCCCNC

Yokohama Specie Bank, San Francisco Branch, YSB Records, JAHA, JCCCNC

In 1916, the San Francisco Branch of Sumitomo Bank also opened its doors for the benefit of local Issei businesses and residents.

Branches in Japan, San Francisco, and Los Angeles Branches. The headquarters, Osaka. We handle hometown remittances swiftly with care. No fees. If you need a remittance application form or anything else, please do not hesitate to contact us.

The mid-1880s witnessed the arrival of many educated Issei youth who were fleeing from state persecution in Japan due to their liberal perspectives and activism. These men were inspired by similar ideas that had previously motivated many members of the Gospel Society to cross the Pacific: an appreciation of modern/western knowledge and ambitions of developing what they perceived as a frontier land in the New World. Known as the “new generation of Meiji,” these youths of humble origin were also heavily influenced by the idea that the Japanese could compete head-on with white men. In San Francisco, many of them worked as student-laborers to support their schooling and livelihoods; others started their own businesses in San Francisco by pooling capital with their friends7.

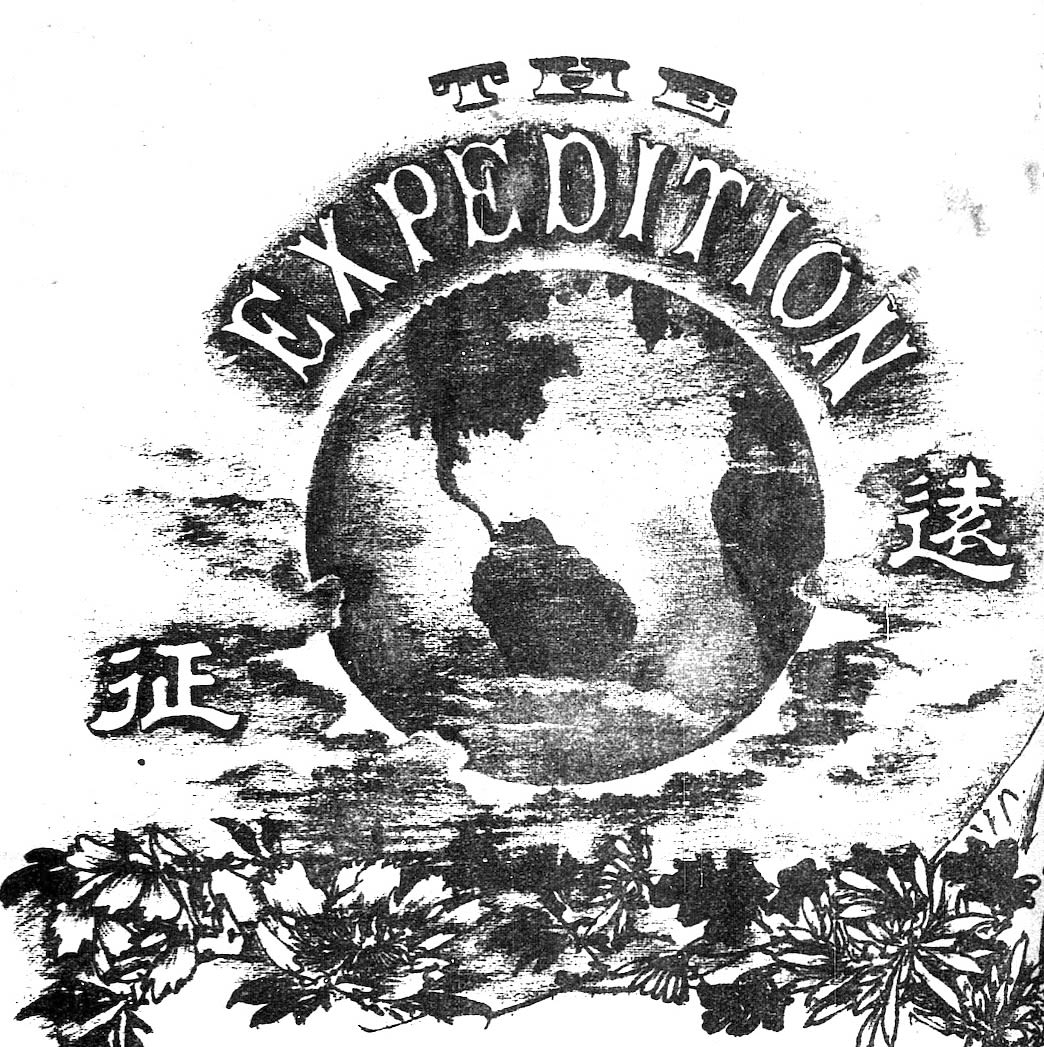

The cover image of the Expedition (September 15, 1891). Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection. "The Expedition,” first published in 1891 by a pioneering group of Japanese individuals in San Francisco, serves as an encouraging beacon for global exploration.

The cover image of the Expedition (September 15, 1891). Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection. "The Expedition,” first published in 1891 by a pioneering group of Japanese individuals in San Francisco, serves as an encouraging beacon for global exploration.

They were also keen on propagating their liberal views among the local Issei and toward their homeland. As a result, these educated youths were responsible for the publication of many newspapers. While most were short-lived, one titled the Shin Sekai survived to emerge as competition to the Nichibei. The rivalry between the two also reinforced the rift between Buddhist Issei and Christian Issei8.

By 1889, the number of the city’s Japanese reached the six-hundred mark.

But within this small community, a community which was already quite diverse in terms of the residents’ backgrounds and occupations, the increase of politically-minded Issei led to growing schisms.

Nevertheless, the presence of the immigrant intelligentsia, and the many newspapers and organizations they supported, rendered San Francisco the intellectual and political center of early Japanese America as well as an economic core. And despite its internal divisions, the community offered strong leadership for the entire Issei population in Northern California as it collectively became a target of severe exclusionist attacks9.

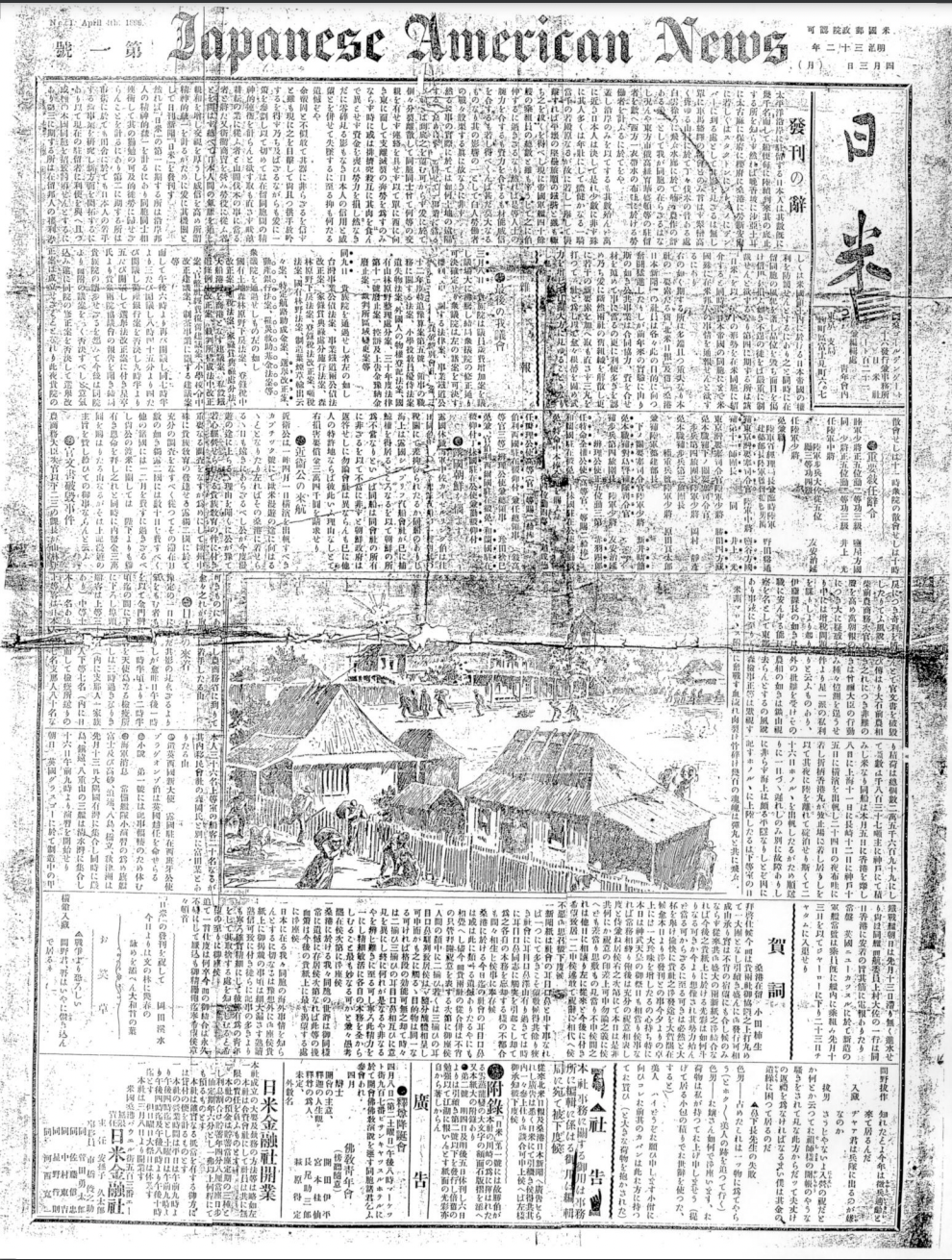

The inaugural issue of the Nichibei Shinbun, April 3, 1899. JAHA Collection and Hoji Shinbun Digital Collecction.

The inaugural issue of the Nichibei Shinbun, April 3, 1899. JAHA Collection and Hoji Shinbun Digital Collecction.

One of the earliest Shin Sekai issues available today. Having been published at 121 Haight Street, it also featured a remittance advertisement by Yokohama Specie Bank, San Francisco office, located at 515 Montgomery Street. JAHA Collection and Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection.

One of the earliest Shin Sekai issues available today. Having been published at 121 Haight Street, it also featured a remittance advertisement by Yokohama Specie Bank, San Francisco office, located at 515 Montgomery Street. JAHA Collection and Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection.

Facing Discrimination

1890s

From the early 1890s onward, the growing visibility of Japanese in San Francisco who were seen as yet another invasion of “Orientals stirred the ire of local white residents who had already successfully pushed for the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. In 1892, when that legislation was about to be renewed by Congress for another ten years, the first organized campaign against the Issei took place in the Golden City. This situation awakened a sense of common identity among local Issei residents, motivating them to seek to overcome their differences in order to combat the collective threat of anti-Japanese agitation. Through the intermediary of the local Japanese consul, immigrant leaders decided to organize the Great Japan Association (Dai-Nihonjinkai). This first all-encompassing ethnic organization in San Francisco signaled a significant step toward the formation of a more cohesive Japanese community under a strong and unified leadership. Known as the Japanese Deliberative Council of America (Zaibei Nihojin Kyogikai), another community-wide organization took its place in response to the discriminatory treatment of Japanese residents during the bubonic plague scare of 1900. The council was instrumental in establishing the Japanese cemetery in Colma in 190110.

Between the 1890s and the 1900s, there was a massive influx of working-class Japanese who had a background in farming—the dekasegi Issei. These new immigrants sought temporary job opportunities in an expanding western agricultural economy.

Keizo Koda’s 7,000-acre farm known for its rice and cotton productions, Dos Palos, California. History of Japanese in America (1940)

Keizo Koda’s 7,000-acre farm known for its rice and cotton productions, Dos Palos, California. History of Japanese in America (1940)

Similar to the practice that had induced Japanese farmers to immigrate to Hawai‘i for plantation work in the mid-1880s, this labor migration brought tens of thousands of laborers to America from Japan’s rural prefectures, such as Hiroshima, Yamaguchi, Fukuoka, and Wakayama. Along with Seattle, San Francisco was a main entry point for these newcomers which resulted in associated businesses booming in the city’s ethnic community11 and which also contributed to the rapid expansion of San Francisco’s Japantown.

Most of these newcomers moved into the interior of northern California and beyond to engage in farm and railroad work. San Francisco’s Issei businesses—boarding houses and inns, grocery and general merchandise stores, and labor-contracting firms—played a vital role in connecting these dekasegi workers with prospective Japanese employers out in the countryside. By facilitating the supply of farm labor, the city’s Japanese community not only filled the financial needs of rural Issei, but also promoted their socioeconomic mobility from workers to entrepreneurs because the YSB and local Issei-owned banks—the latter being often backed by the former—provided loans for their agricultural endeavors, such as large-scale rice farming12.

As these multifaceted roles of San Francisco underscore, the city’s ethnic community occupied a significant place in the experiences of Japanese immigrants in Northern California. Its importance was also reinforced by the fact that the city was home to the Japanese consulate and major Japanese corporate interests, like YSB. Indeed, the partnership that the local Issei maintained with Japan’s diplomats and business elites helped solidify their leadership when the Japanese in America collectively faced the need to mobilize against the intensifying political movement that strove to exclude them as it had done with the Chinese a few decades earlier13.

Organizing Community

1900s

In 1905, the San Francisco Board of Education ordered Japanese pupils to attend the Oriental School reserved for the Chinese, thus causing a diplomatic crisis between the United States and Japan. The negotiations between Washington and Tokyo resulted in the US-Japan Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907-1908, which ended the coming of working-class dekasegi immigrants but unexpectedly catalyzed the influx of young Japanese women married to resident male Issei (known as “picture brides”). This development resulted in the emergence of many immigrant settler families and the rapid increase of US-born children—Nisei—during the 1910s and later. Now, along with the constant threat of racism, the community also had to grapple with new challenges and needs, such as Nisei’s education (see Morimoto essay)15.

In this context, San Francisco Issei leaders, such as Kyūtarō Abiko and Kinji Ushijima (Potato King “George Shima”), cooperated with the Japanese consul and the branch managers of YBS and Mitsui to organize the Japanese Association of America (JAA: Zaibei Nihonjinkai) in San Francisco. The goal was to keep all Issei united against exclusionist attacks and pursue mutual prosperity as American residents under its centralized control. Local Japanese association affiliates were subsequently formed in localities with a significant presence of Issei residents throughout California and beyond. With the JAA as the umbrella organization, an expanding network of Japanese associations made it possible to create a number of tight-knit communities of first-generation Japanese Americans across the US West16. After the JAA’s establishment in 1908, the ethnic identity and consciousness of the Issei tended to revolve around the dictates of the San Francisco leadership, which was also eager to maintain harmonious relations with representatives of the Japanese government and industry.

Council Members of the San Francisco Japanese Association, 1931. Iwao Shimizu Papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Courtesy of the Shimizu family.

Council Members of the San Francisco Japanese Association, 1931. Iwao Shimizu Papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Courtesy of the Shimizu family.

After the Quake

1910s

The cohesion of the prewar Japanese community entailed multilayered linkages and bonds forged by Issei membership in other ethnic organizations and groups as well. Some were spiritual in nature, like Buddhist and Christian churches; others were socioeconomic, like trade and occupation-based associations. From the 1910s, the increase of US-born Nisei also paved the way to the opening of many Japanese-language schools, including Kinmon Gakuen (1911). The prefectural associations (kenjinkai) also flourished, since they embodied the Issei’s enduring sense of connections to their families and birthplaces in Japan., Another part of these connections, one that constituted an important aspect of the Japanese prewar immigrant experience, was the prevalent act of sending remittances back home.. It is for this reason that not only the formal financial institutions, such as YSB and Sumitomo Bank, but also many Issei-owned businesses, offered remittance services for the convenience of local residents)17.

The first decade of the twentieth century also brought a significant change to the physical locations of the Japanese community in San Francisco. Until the great earthquake of 1906 decimated the original Japantown, the area along “DuPont Street” near Chinatown (later renamed Grant Avenue) was a geographic center of Issei businesses and residences (. After the disaster, many art-and-curio shops managed to reopen in the old Japantown area. However, most Issei enterprises moved west to the several blocks surrounding Post Street and Buchanan Street (present-day Japantown Peace Plaza), which came to be known as “Upper Japantown.”

The Great Earthquake, San Fracisco. Teraoka and Takeshita family papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives.

The Great Earthquake, San Fracisco. Teraoka and Takeshita family papers, Hoover Institution Library & Archives.

A Community Grows

1920–1930s

By the 1930s, more than two hundred ethnic stores, several hundred private residences, and numerous community organizations (Japanese-language schools, religious institutions, and newspapers) were located in this general area18. Meanwhile, after 1906, Issei-owned international trading firms, as well as YSB and other Japanese corporate subsidiaries, set up their offices within the city’s main business district east of Montgomery Street (See about the importance of trading companies for Japan). There was also a concentration of Japanese businesses and homes in the vicinity of South Park19. Despite the contractions experienced by the ethnic community due to immigration exclusion (1924) and the Great Depression (1929), San Francisco remained a political, economic, and cultural hub of prewar Japanese America.

In 1939, there were still 6,716 Japanese in the city: 2,191 Issei men; 735 Issei women; 1,120 Nisei men; and 2,600 Nisei women20.

This essay narrated the pivotal place that San Francisco occupied in the early history of Japanese Americans—its largely-forgotten Issei era before the destruction of their livelihoods and residences by the mass incarceration of 1942. The city’s ethnic community was home to such important organizations as the Japanese Association of America, the headquarters of the Buddhist Churches and various ethnic Christian groups, renowned Japanese heritage institutions, Japanese-language schools for the Nisei, thriving Japanese businesses, and financial institutions that catered to the needs of Japanese and other Americans inside and outside San Francisco. Japanese America was also connected to Japan and the rest of the Asia-Pacific economically and culturally via these community-based organizations.

The JAHA-Oka collection serves as a knowledge base of historical information that will allow future generations of Japanese Americans (and others) to research and discover this important history—a history that wartime racism almost destroyed. Fortunately, this history has been restored and preserved through the dogged efforts of many individuals and organizations, including the late Mr. Seizo Oka and supporters and staff of the JCCCNC.

The records of the Yokohama Specie Bank's (YSB) San Francisco branch, currently housed in the Japanese American Historical Archives - Seizo Oka Collection (JAHA) at the Japanese American Cultural Center of Northern California (JCCCNC), provide a unique window into the inner workings of the Japanese American business community. This aspect of history is often overlooked in traditional historical accounts, offering a nuanced understanding of the Japanese American community, its intricate social networks, hierarchical structures, business objectives, and entertainment activities during the era of prohibition.